I wrote this blog as I was trying to understand why the death of Cecil the lion upset me (and many others) so much. The link between Galen and Cecil, I admit, is not perfectly obvious.

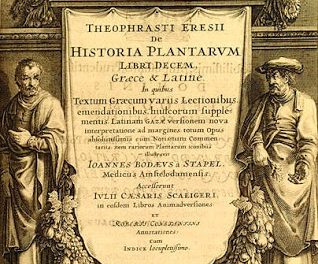

In most of his texts, Galen (129-c.216 AD) likes to show off his classical culture. Thus many famous texts, authors, characters or heroes appear in his “medical” oeuvre. His choice authors were Homer, Euripides, Thucydides and, to a lesser extent, archaic poets. He also valued highly the comic playwright Aristophanes, for a whole load of reasons, some of which medical historical – Aristophanes helps you understand medical texts of the classical period, he argued. But Galen’s poetry culture is indeed impressive.

At the heart of this cultural display lie some essential Greek virtues: beauty and courage. Indeed, beauty and other virtues are consensual among the public. Beauty appears extensively in Galen’s two most epideictic works, the Protreptic and On the usefulness of the parts of the body: to him, beauty is divine and can be found in every aspect of the Creation. Indeed, whatever the Demiurge (or Providential Nature) intended, is necessarily beautiful. Galen praises the Sun, the most beautiful body of the universe, the eye, as the most beautiful part of the human body, and the humble foot, as its often overlooked, undervalued counterpart (Galen, On the usefulness of the parts of the body, III, 10). His intention is to highlight the quintessential beauty of the divine Creation through one particular example best known to him: human anatomy. Galen’s argument covers seventeen books, and virtually every known body part. It is a thorough exercise in praise rhetoric, and perhaps even in some form of religious rhetoric, not just a medical treatise. Beauty is a serious matter.

But in another treatise (On the doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato, IV, 6, 9-10 – De Lacy vol. I, p. 272-273), Galen suggests yet something else about beauty: there is something so powerful, so compelling about beauty, that even the most determined murderer must lay its weapon down in front of it. Such was Menelaos, says Euripides, quoted by Galen, as he stormed into Priam’s palace with the firm intention to kill Helen:

“When you caught sight of her breast you dropped your sword

And took her kiss, fawning on the shameless traitor” (Eur. Andr. 629-630)

Struck by Helen’s beauty, Menelaos lets go of his sword. Galen doesn’t care much about Helen, and has only contempt for Menelaos’ “softness of the soul” – his point is to argue with long-dead Chrysippus about the weakness of the soul. But that beauty should win in any contest is kind of commonplace in Greek literature: the excessively beautiful courtesan Phrynè allegedly won her case when her defender, Hyperides, ripped off her clothes in the tribunal, to show off her beauty. Not only does beauty speak for itself, but it shuts the enemy’s mouth down, and it puts swords back into their sheaths. And that’s how it should work, right?

Naturally, things rarely turn out this way in real life. Many beautiful creatures experience cruel death. At times, it is indeed recognisable as Nature’s own design – as Galen would put it. Lions eat graceful gazelles, cats kill those lovely birds in your garden. But at other times, it seems incredibly unfair: human cruelty towards other humans or living creatures is often at stake. Cecil, Zimbabwe’s most famous and popular lion, experienced this tragically when a rich [insert your favoured insult here] recently baited the beautiful animal out of the national park, then shot him with a cross-bow, and tracked him for 40 hours until he shot him at point blank with a gun, skinned him and cut his head off. So much for the most beautiful lion of Zimbabwe, and perhaps of Africa. Such poachers are not rare; and the fate of Cecil is not uncommon. Thousands of theoretically protected animals die each year for a few individuals’ profit. Think of the plight of elephants, tigers and pangolins. But what, in Cecil’s story, is so indescribably sad, and moved the world to tears?

Cecil the lion epitomised natural beauty in a way that few creatures do. Photographed by thousands of tourists each year, he was more than a furry poster boy: he embodied Nature’s perfection. An unusual mix of beauty, and of the qualities traditionally attributed to lions: courage, and a certain air of royalty. That lions are the most courageous of animals (including humans) is another commonplace in Greek literature, one that Galen, again, likes to remind us when praising Nature for distributing qualities evenly among creatures (On the usefulness of the parts of the body, I, 2). But Cecil’s murderer caught him by treachery and cowardice, dragging him out of the safe place where he was thriving and then hunting him without mercy until the disgusting final humiliation took place. This ultimate reversal of Nature’s intended order achieved as much public outrage as the simple destruction of that beauty. While the world would have excused endangered people for killing a lion to protect their own lives or their herds, the cowardly murder and humiliation of the great Cecil, who embodied beauty and courage as well as an ideal natural world, is inexcusable. Cecil belonged to everyone and anyone. He was everybody’s big cat, everybody’s share of natural beauty. He was supposed to be safe, lead a beautiful life, and to continue existing for the enjoyment of all. It wasn’t for an arrogant hunting [beep!] to kill him. It is all too understandable that everybody should grieve for his martyrdom. Besides, he had a name, like your pets or mine. Cecil’s horrible death suddenly embodies everything that is wrong with humans’ relationship with Nature.

Galen (and ancient Greeks in general) showed little concern for animal welfare; Galen even advocates hunting as an excellent sport for those who can afford it; he also eviscerated and killed many animals himself for the sake of dissection and vivisection. Animals were routinely sacrificed for all sorts of purposes. Only a few ancient sects refrained from consuming animal flesh and from hurting the living. And in many ways, the ancients began theorising man’s superiority over other animals (through thinking and talking, thus discovering the arts, making weapons, etc). Clearly, one shouldn’t look for animal rights in antiquity. But ancient texts such as Galen’s On the usefulness of the parts of the body are also here to remind us that, whichever god(s) you believe in (and Galen is careful to name none), Nature is bigger than man. Troubling its order is, and should remain a taboo. Killing for the sake of it, an unspeakable offence.

R. I. P. Cecil the lion.